“… One day I would cross a threshold into an enormous park, an endless and beautiful park; in this park one ingenious invention would succeed another. Plants and music would follow in lovely mathematical alternation, delightful to the ear and answering to the utmost notions of delicacy; but this park was not there to be used, or wandered about in, because it consisted of a thousand and one small and miniscule square and rectangular and circular islets, pieces of lawn, each of them so individual that I would be unable to leave the one on which I was standing. In each case, there is a breadth and depth of water that prevents one from hopping from one island to another in my imagining. On the piece of grass which one has reached, how is a mystery, on which one has woken up, and where one is compelled to stay, one would finally perish of hunger and thirst. One’s longing to be able to walk through the whole park is finally deadly.”

(Thomas Bernhard, Frost, trans. Michael Hofmann, Random House, 2008.)

In this novel from the 1960s, Thomas Bernhard describes the cultural isolation of all our modern disciplines, from chemistry to physics to geometry to philosophy to art. Part of this is the hunger, or thirst, to make everything describable or measurable. But painting isn’t like that and, in the face of painting, the modern viewer may easily become like Thomas Bernhard’s character, standing on his isolated island and looking out at the universe, not in wonderment but in a kind of bewilderment that often slides into danger. What kind of danger? The danger of not knowing what this is all about. For painting isn’t articulable. It is a process that must be trusted.

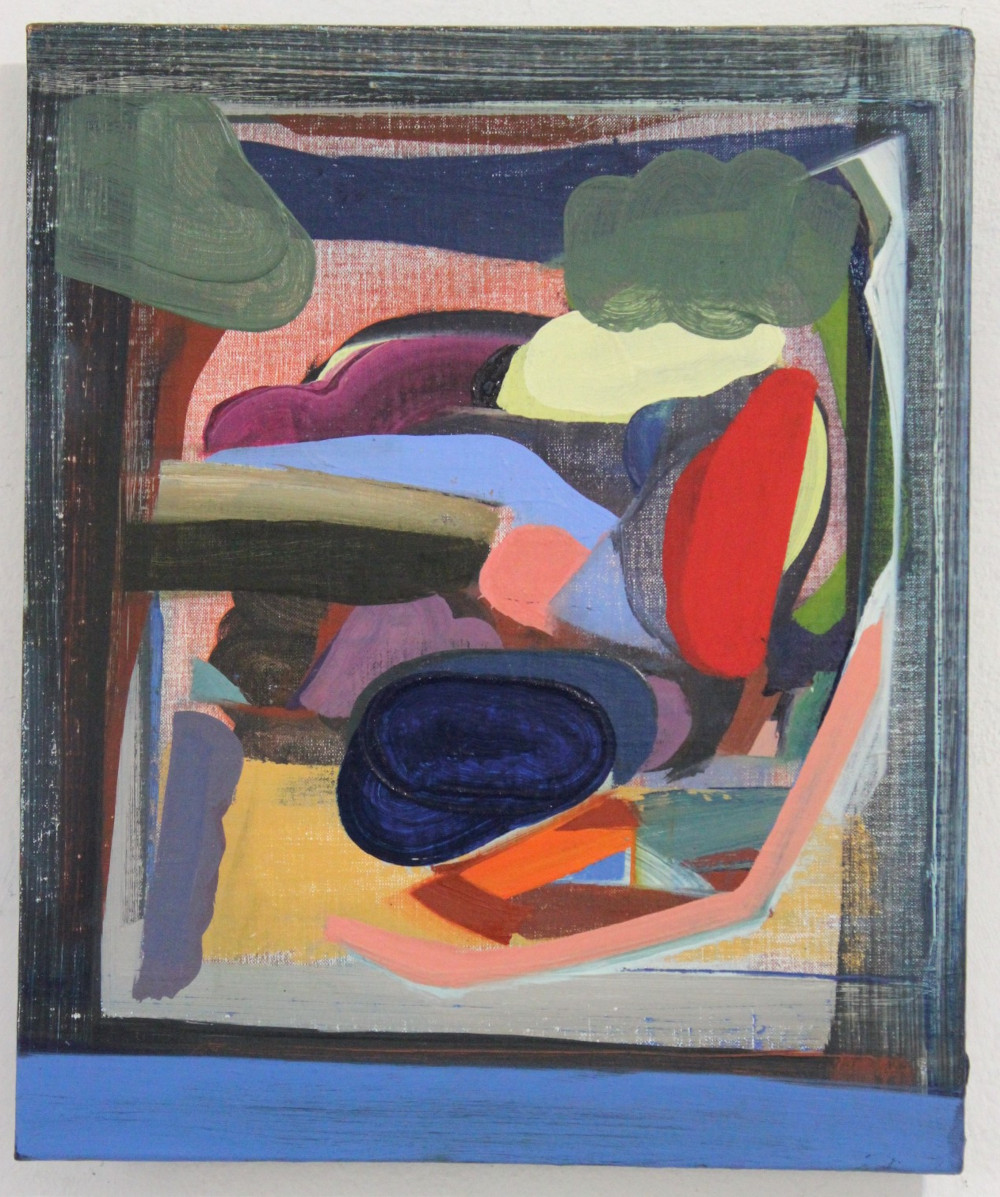

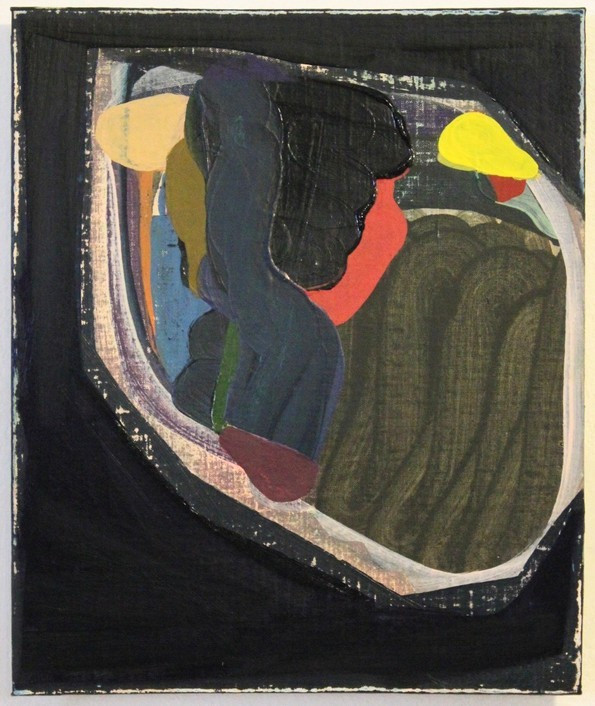

The painter has learned knowledge, body knowledge as well as head knowledge. Through repetition the body learns and, in painting, there is a physicality, an earthiness even. Paintings take place over time and, then, the painting is installed. It is placed and it must command its space. Sinéad Aldridge’s paintings have now come to command their space.Looking at these paintings, we are seeing that painting is knitted into the painter’s life. Sinéad paints for maybe three or four hours and then she moves between this and the many everyday chores of life: buying bread, maybe, or travelling on a tram … then she returns to her paintings with this in tow. We must scratch, we must scrape beneath the painting, to see what these paintings show.

What do Sinéad’s paintings show?

They are the reverse of veils and, instead of hiding, there is a revealing. The paint layers up and, then, every aspect of life, from memories to chores to peripheral vision to looking, looking, looking becomes a collage inside the layered paint, a collage put on linen and then built over and over. It is there, even when you can’t see it anymore, like the tree rings that are hiding underneath the bark. You know they’re there so that you don’t have to look. You can just assume. Then the hidden depth … gives depth. It stays there like a ripple. Where does the ripple lie? In the water? In the fabric of the world?

Where is it? It is simply there. Then, to give it a name, press a finger against the ripple to halt it in its flow. Is it like putting a finger against someone’s lip when you’ve decided that they have finished speaking? It is enough.

The geometry in Sinéad’s paintings can sometimes seem carnivalesque. I imagine Tarot cards filled with geometries and with human figures as well. Angular shapes bring a sense of foreboding to her paintings, especially when the colours are dark. Brighter colours are different, even when they have the same shapes as the darker ones. These are less foreboding and are like the shards of a mosaic, the very building blocks of a mosaic translated into paint, then vastly increased in size. They are magnified. These are not like the pixels from print or computer technology. Those tend to be uniform in shape and size, like something the Atomists coughed up for us. But Sinéad’s shards have deep personality. The triangles stretch beyond mere geometry into something else, into the origin of things, maybe into the mosaics in San Vitale, in Ravenna.

But Sinéad’s paintings are not just about shards of memory. Sometimes they spill over the frame and, then, outside the frame they become the hidden painting. What is spilling beyond the frame? Is it a shadow thrown across the surface, a presence?

Look carefully.

There are female shapes, like hidden madonnas. The pure form of the female figure sits among the hidden foliages, the undergrowth. Paint is shaped and built into the earthy and the physical, veiled and layered paint, then into series and series of series. These paintings are evolving as we watch them. Look again and there is the feeling of something familiar and yet other. The painting acts like a kind of conscience between us all.

It whispers to us.

Sinéad’s paintings are speaking and sometimes their words are shaped and framed as quotations within quotations, as framing within the frame, an interior gaze bracketing a mode of reflection. This could be a dream (in Blake) or paradise before the fall. It might be the circus (Zirkus in Tempelhofer Feld) or the magic carpet. But I cannot be prescriptive here, and I won’t be. These are paintings after all and not my words.

But there is a quotation I read once about the early Renaissance. It is the question: “Is the universe still a work of art that we can perceive in a painting?” Do these paintings coalesce and become a movement in time? Are they flowing like water, like shimmering veils? Look into these paintings and time is going away and who knows where it is going to?

No place. No time. No thing. Nothing. Silence.

An inhalation without an exhalation.

Sheaths of time form over these paintings. As Osip Mandelstam said, “… its language made no sense and had no point.” Yet I hear a whisper and I know it can’t be true. Existence is a problem, but it is all we’ve got. The physical is it. The earthiness. The paint and linen are there. Then, Sinéad handed me a quotation from Terry Eagleton: “ …. It is not simply a matter of treating strangers as neighbours but treating oneself as strange – of recognising at the core of one’s being an implacable demand which is ultimately inscrutable, and which is the true ground, beyond the mirror on which human subjects can effect an encounter. It is this which Hegel knew as Geist, psychoanalysis knows as Real, and the Judaeo-Christian tradition as the love of God. For all the admirable tender-heartedness of an imaginary ethics, it is a horror and a splendour which lies beyond its limited comprehension” (Terry Eagleton, Trouble with Strangers, Wiley-Blackwell, 2008, 59-60).

Sinéad’s paintings are not in some inscrutable place, some no place. They are installed here and their veils expose rather than hide. What do they expose for us? They expose the ripple in the water, the rings inside the tree. They are the veils of the physical and earthy paint that reveal all that there is. They are the shards, the park, the dream, the journey and the after image. And yes, the universe is still a work of art that we can perceive in a painting.

Dr Tony Partridge

October 2015