No one believes it is happening now.

Only a white-haired old man, who would be a prophet

Yet is not a prophet, for he’s much too busy,

Repeats while he binds his tomatoes:

There will be no other end of the world,

There will be no other end of the world. “

Czeslaw Milosz Warsaw, 1944

Artists find it hard to situate what they do within this world of targets, numbers, the value per head, public subsidies, responsibility, art for all, and so on. Not all flatter the society around them. Many feel alienated. Many, like Antonin Artaud or Nietzsche before them, have joined the grandiose task of “transvaluation of values”. I read it as freedom for imagination. Not only Schiller but also younger artists thought about that. The other day I came across a quote from Czeslaw Milosz: “The creative act is associated with a feeling of freedom that is, in its turn, born in the struggle against an apparently invisible resistance. Whoever truly creates is alone. . . . The creative man has no choice but to trust his inner command and place everything at stake in order to express what seems to him to be true”

Milosz’s own poem ends with

No one believes it is happening now.

Only a white-haired old man, who would be a prophet

Yet is not a prophet, for he’s much too busy,

Repeats while he binds his tomatoes:

There will be no other end of the world,

There will be no other end of the world.

Warsaw, 1944

The title of the exhibition of fifteen paintings by Sinead Aldridge at Fenderesky sky is falling occupies a similar niche and is probably a chance meeting of her life experience and her imagination to make something visible, which is not visible in normal life.

Leonardo and Poussin strived to elucidate the similar ambition of poetry and painting: painting is mute poetry for one, while the other issues a clarion call ut pictura poesis.

Ubiquitous, are the commentaries on Kandinsky’s envy of Schoenberg’s freedom.

This morning an email run over the relationship between painting and music once more.

(Jackson Arn on https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-music-motivated-artists-matisse-kandinsky-reinvent-painting?)

Jackson Arn states that the earliest formulation came from Walter Pater in 1877 “All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music.”

The synesthesia of seeing and hearing, seeing and poetry is possible whenever.

Walking around the gallery with “the sky is falling” in mind created confusion – which on the second visit disappeared. At first, the hard-hitting images, the arrogant brush, violent clashes of hues, when titles felt irrelevant, evoked concern about the artist, not just about the paintings.

The first sensual bridge I built when I recognized the red hue snaking the way favoured by Andre Derain (Les Fauves). For example Les Arbres,1906, in the Albright-Knox collection. (downloaded from Wikiart.org)

Some admission is also in the title. Les Fauves means wild things (painters).

What is made visible is an intense torment. In these images and of these images. The yellow, the lemony anemic yellow, morphs into a cloister of gothic windows, manmade forms signaling religion, the guard the weeping monks keep on the tomb of the Duke of Burgundy at Dijon. Thoughts about eternity.

Aldridge also shares with the medieval painting a device to carve a niche behind the picture’s plane:

That (cage like) space is for meditation, prayers, beliefs, and it is visible between the trunks of trees, the trees that hold at bay, with some difficulty, the waves of a possible deluge.

Another nod to representation is what could be a figure partly hidden behind the frame on the right: The blue oval fills the place of a head, the voluminous black covers what could be a figure, like an observer materialising above the flat ribbon of red.

The slivers of yellow appear here and there without a willingness to share why, as if bubbled through from the depth of the Earth. They appear independent from the main composition (instead of forging it!). In some way, they are there to minimize the image’s clarity. They look like being there by chance…

All of the paintings feed on Modernism of the early 20th C while managing to look from its end. Heavy divided marks left by saturated wide brush are not friendly to the minutiae, like those yellow slivers in the dark areas of the 2018 painting above. Below is the signature painting that shares its title with the name of the whole exhibition.

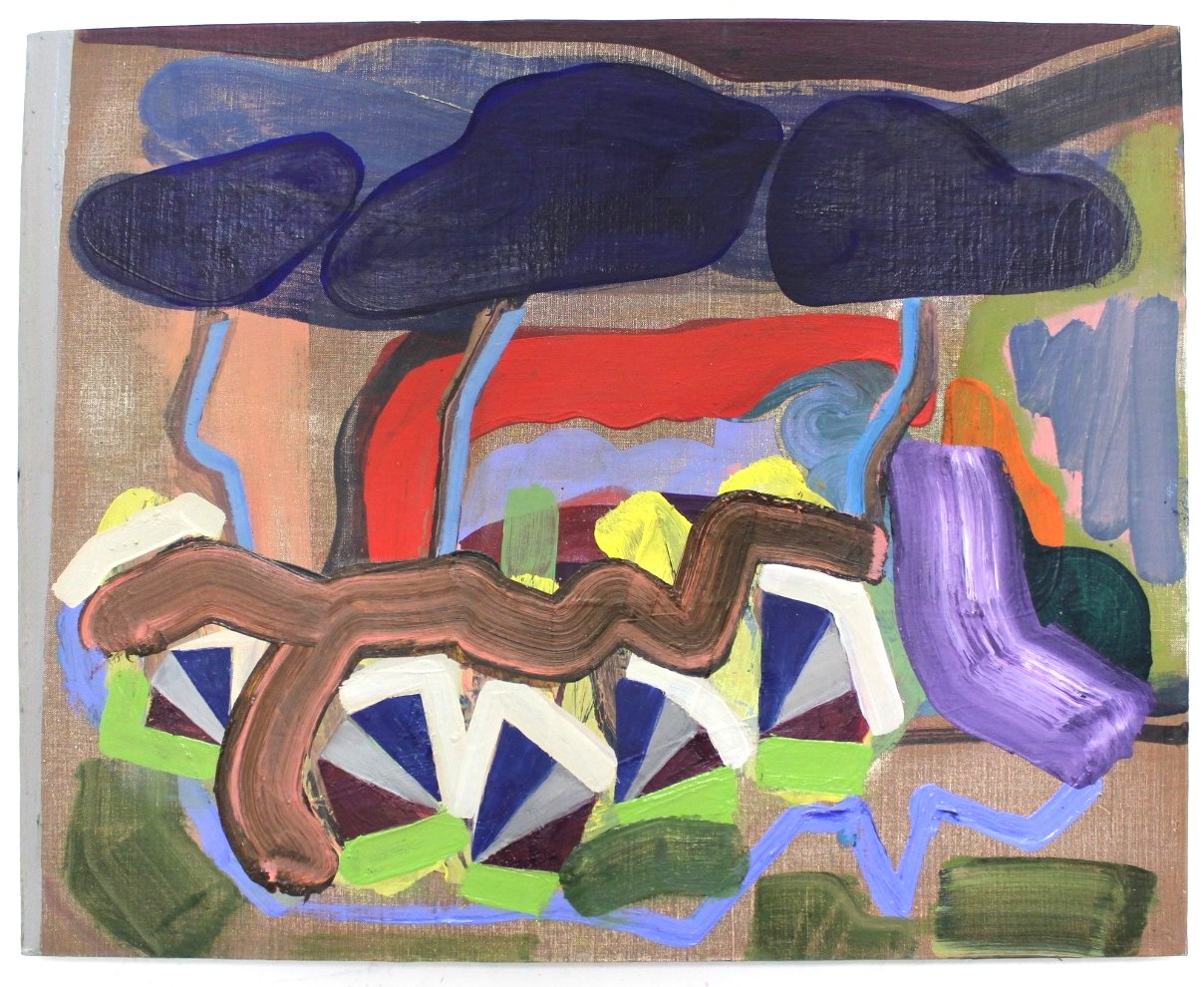

The above namesake of the exhibition title reworks some motives from the previous painting, however, with lesser attention to its pedigree. The foreground is where I stand, not inside the frame, due to the blue wiggles ending invisibly behind the lower frame. Even horizontally, the image is behind that Albertian window… in another space where it continues behind the visible rectangle, like a ribbon of a film. The tree trunks may be trees in the storm or visible synchronised lightening. It depends whether the voluminous mass above is thought of as crowns or clouds.

The view is akin to a view from a train window, or via a mobile phone camera. It is a fragment. A whimsical one. It allows the glimpse of blue sea and white sky behind the earth hues placed by fully saturated brush on automat. There is a lot of heavy hanging matter that sucks the space out, the exception being that view to a distance. Being placed very near (around) the golden section it is compositionally and visually significant.

It is as if the painter enjoyed confusing the viewer by that messy spatial organization. The saturated thick brush is not willing to respect any demands for acute characteristic. It is summarising and recklessly free.

Hence it can get out of hand.

It appears to me like an interior, like a scene from a theatre. Near the lower frame, flowing from the left to the right the confident pink divides space, small area for the listeners, seated viewers (stones), then the stage with bright yellow prompt box. (Or is it an eager listener?) A blue head (deformed like in Munch’s Scream) sits directly on kneeling spiky legs and appears communicating with the invisible audience. There the narrative part ends. The rest is anchored in the power of hues to lie: the small yellow rectangle creates another space with green and pink between the two clumsy black that craftily create a gap for the red to point the way to the blue, which insists in turning back inside. The pinks and grey are like torrents that lost their raison d’etre and became stationary. The black is swallowing the space like an incorrigible glutton. The scene is that of the fragmented world, in which the speakers need that yellow prompt, whatever it stands for.

Like music, these images are not a narrative, though they exploit some clues to and of it. Equally, insecure is the relationship between what is made visible and what the words of the title may suggest.

The quietest of all compositions, it takes advantage of indirect light, emanating, like in a Matisse, from each hue in some equivalent way, like early morning light moving from black to white, though not gradually. This image appears to me as strongly considered, if reluctant to depart its meaning, it is difficult to decide what it makes visible. Maybe that is its tenor. Not a state of mind? The blue certainly invites quiet reminiscing around and over the obstacles in saturated hues of shifting modulations as they stand parallel to each other. Parallels never meet. They only appear to do so. And that is the special space for imagining.

A different approach to space is visible in an older image below, which looks back to the established composition of a portrait surrounded by abstract ground.

What looks like a hat gives away some link to the title. The central composition makes it more narrative by singling out the centrally placed assemblage of hues. The background is just about there, playful, rococo – light. The intrusion of nonsense has become a conditio sine qua non, here both verticals on the right, the indigo blue curve and the gray-greenish one, just travel from nowhere to nowhere. It evokes jolly masquerade by insisting that nonsense keeps playing with intention.

The concern about boundaries had surfaced in an assemblage of biomorphic form and an acute, undernourished, geometry.

The hard edge clean geometry of small triangles is both central and not. I find the plethora of triangles at the edges being both pushed away, in spite of that stubbornly staying. The yellow ones are about to be crushed by the huge amorphous masses. The front plane is swallowed by two amorphous blobs of almost an organic matter in anemic violet, poised as if having an argument.

Yes, these shapes are quite audible. Possibly, they rehearse the question we all share:

How to preserve an inner sense of self against the relentless pressing-in of the world’s demands?

The answer is in fragments of each of the exhibits. Incomplete. A task set as a transvaluation of values luckily includes disestablishing the instrumental value of art.

I could be wrong, but maybe a smaller brush will manage the pain of sensitivity to the growing gaps between intentions and reality that we all face daily. Aldridge has managed to hold forces of the hues set out for conflict, not by taming them, but by confronting them with a difference. The evidence is visible even in the tiny yellow slivers where the wild things are.

And yes, she did not manage to mend the wounded world. Could anyone?

Dr Slavka Sverakova 2019